The Death

January 8 was the one year anniversary of Steven’s Death, and I’m hoping to complete this blog post about it that was begun on February 6, 2020.

I’ve written it so many times, and it will never be enough. I’ll never get it exactly right. Yet the longer I wait the more the memories in my mind lighten their hold. I don’t want to lose the memories, and so I write.

I still miss him. He would have loved to hear stories of the chickens and Mocha. He would have had theories about the virus and God knows I would love to hear his opinions about the attempted coup as someone who was a military veteran.

I’m doing some volunteer work today, and learning with the children, and tonight I’ll have a drink in his honor, though he stopped drinking years ago.

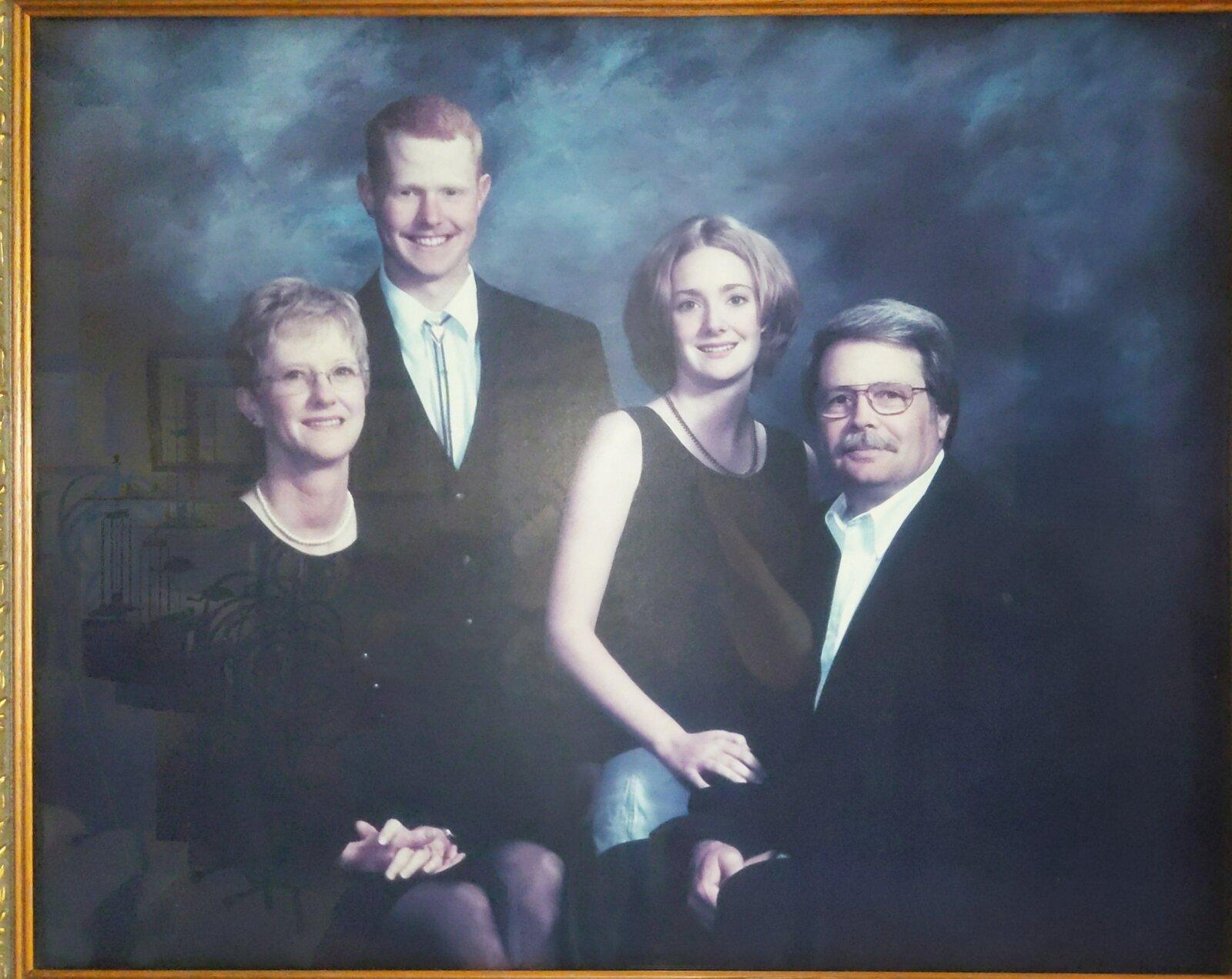

And I’ll be sad. I’m one of his loved ones who gets to just be sad without the weight of tangled relationships and difficult personalities. He was my brother and I miss him.

The rest of the story:

I’ve been pondering how to write of Steven’s death and of his life. Some stories we want to talk over again and again; maybe the telling takes away the pain, or maybe it solidifies the memories in our brain.

Both of these may be why I’ve been writing and rewriting these posts in my head. I don’t want to forget and I don’t want to get it wrong and I need to write it down to continue moving forward toward peace.

As I sit here on May 18, 2020, I realize I have offered sincere words of sympathy to two of my neighbors upon learning of the death of the father of one in November of last year, and a spouse of the other, also in 2019.

“If the deaths were going to happen, what a blessing for them to have been before Covid-19 came knocking.” I thought in both instances. Then I realized my gratitude around Steven’s death for that, too. To not have been part of his passing would have been such a huge loss. It would have compounded the pain of his death in so many ways.

Steven called me on December 31, 2019 in the afternoon. His voice sounded normal, but it was unusual for him to call. We usually text once or twice a day.

We were having friends over for our regular New Year’s Eve Party, so I almost didn’t answer in the rush of getting ready for that. But I did.

“How’s your day?” He asked.

“Good,” I replied.

“Well, that might not last much longer,” he said quietly.

He was just getting home from an appointment with his pulmonologist. She had told him he probably had 5-6 months left to live.

“I’m not telling anyone else, Kid.” (He often called me “Kid.”) “I’ll talk to the kids (his son and daughter), but don’t tell Mom yet.”

I had a trip planned to fly down to go with him to a doctor’s appointment the following week and to spend a couple extra days with my brother and sister-in-law, just by myself, and he referenced that trip.

“If you don’t want to come down, I understand. I’m not going to that appointment now. There’s no need.”

“Of course I’m coming down,” I said. “I want to be with you.”

We had our party that night. Eddie’s dad was in the hospital, Cash was in an induced coma in Iowa City trying to get his seizures under control, and I would be flying down to spend time with my dying brother the following Monday. We weren’t the liveliest crew, but it was good to be together.

Then on New Year’s Day, Steven crashed. Faye ended up calling for an ambulance around 3 in the morning. My SIL texted me to let me know they had him in the ICU. My nephew and his wife flew down as soon as they could, and my niece followed soon after.

They all kept me informed, and there was initially hope he would bounce back to get those few promised months.

My brother asked to have pictures sent to me so I knew how he was doing. He knows I worry.

They were able to take him home on Friday, Jan. 3. My niece kept me updated as they got home hospice set up and we discussed plans. My family was headed to Chattanooga for the weekend, and my feelings were so mixed.

I flew down to Las Vegas on Monday, January 6, not really sure what I would find when I got to their house.

It was my first time on a plane in a long time, and the flight home would be my last flight for a very long time, but we had little clue as a nation what was breathing its way toward us.

I picked up the little red car I had rented. It was larger than I needed since I had gotten it when I had planned on driving the three of us into Las Vegas for Steven’s appointment.

The drive from Las Vegas to their home in Arizona is beautiful in that dry desert way.

I had been texting with my niece to keep her updated on my progress and she met me outside as I parked the car by the house. I blanched as she told me Steven had become unresponsive.

We went inside to greet my sister-in-law, my nephew, and his wife. I had never gotten to meet her before and liked her immediately.

And thus began the next several days of that strange in-between time that can so often come with encroaching death.

James and Danielle had to leave the next day for an important job interview for James. This interview was the reason Steven had asked me to take him to the doctor in the first place.

James had been coming down to help with appointments as much as he could, but needed this one time away for this fantastic job. (James did get the job and he loves it.)

Though I hated that they had to leave, I was so very grateful that the timing ended up allowing me the opportunity to be a part of this sacred time.

We spent the day visiting, caring for Steven, planning, and waiting.

It turned out that Steven was unresponsive, until he suddenly wasn’t. We eventually realized that one of the meds he’d been prescribed by hospice, which was supposed to help keep him relaxed, could in some people cause agitation. Turns out he was “some people.”

So there would be hours of rest and calm until he was suddenly awake and agitated. Very agitated.

James and Faye had seen and dealt with this while he was in the hospital. It is exhausting. The whole process of death is exhausting and numbing and wearing. You know the end is coming, but there’s no timeline. There’s really no end in sight and you have no way of knowing when it’s okay to rest. There really is no peace, until finally there is the final peace.

I took on nighttime duty so that everyone else could rest. I sat in a comfy chair next to his bed and watched him breathe, adjusted his cannula, swabbed his tongue and lips, read books, wrote down the things he was saying, gave him his meds, told him I loved him.

Faye would rest, then handle everything during the day while Patricia planned. She worked her way through documents and records, making sure things were in place.

I would sleep for a couple hours, then be up to help again.

I’m forever grateful there were just enough moments of lucidity for me to know that he saw that I was there and that he told me he loved me. You treasure those brief moments when the eyes seem to clear and the person you know is suddenly there, even if just for a minute.

There was a wonderful hospice nurse who came in each day to shave and bathe Steven. That was an example of the relief professional caregivers provide. We would have taken care of those personal needs, my SIL and I, but for that final barrier of privacy and intimacy to be maintained is a gift to the family.

It was a gift of a memory I will forever cherish that Steven, Mom, George, and I gathered to wash and dress Dad after he died, before the funeral home came to wheel him away. Steven, who had been an orderly in the hospital where he and Mom both worked before he left for the military, did most of the work, lovingly combing Dad’s hair as the final act as we all stood together around the bed.

But in this instance of Steven’s death, having someone else care for his physical needs allowed us a measure of freedom.

I never met her because she came during the time I slept in the afternoon so that I could take the night shift and allow the others to sleep as they could.

In those strange nighttime hours, he didn’t generally progress to full agitation as he did during the day. The daytime could bring yelling and wild-eyed stares, but the night brought long, rambling, unconnected phrases and sentences. He spoke of work and co-workers, fragments of sentences and memories all melding together in whatever way his brain needed to process before it could finally breathe its last.

And then came his final hours. The hospice caregiver had told Faye and Patricia that it would be coming soon when she came that day for his bath and shave.

There is something comforting, yet sad to me about the sameness of death. We each want to feel so unique and special, but in the end, certain types of death follow a pattern and the Hospice folks have seen so much they know how the river flows.

We were watching “Where’d You Go, Bernadette,” and I was sitting in the chair I had moved out of alignment so I could rest in it and still see Steven’s every move. At some point I looked in, went to see him, and something had changed. His breathing was gurgling, and he was looking grayer.

There was a fluttery spot at the base of his throat. The spot right above the top of the sternum; the little hollow in the front of your neck. Such a vulnerable spot.

As his wife and I waited for what would be his final breath, I watched that fluttering spot. At this point, when he would take a breath it would be a great gulp; and by watching that spot I could tell when the great gulp was coming.

And I knew that when that fluttering stopped, so had Steven.

It took a long time. Or it seemed to.

It might have been minutes, it might have been an hour.

It’s been a year now and I don’t remember. And time flows differently when you are watching life flutter away. I wanted to notice the final breath, but you don’t know if it will be the final breath.

I asked Faye if she wanted me to leave, and she generously allowed me to stay. We were all talking to him, reassuring him he was safe.

And then the last flutter was gone.

Faye checked for a pulse, and there was none.

We three breathed that collective sigh.

For some moments and the death of some people, there is also relief. The exhaustion of the last few days is weighing so heavily on you. (And some people carry this weight for months or even years.) And in some cases, the person was difficult in life and that brings an upswelling of emotions, too.

But in this moment, we just breathed.

Faye noted the time of death, although the official record is when the hospice nurse calls it.

She called hospice and the wonderful, kind, loving hospice nurse came and stayed with us. She listened to Faye and Patty tell stories. She gathered up the items that wouldn’t be needed, she called the funeral home.

These were moments I was only there to witness. He was my brother, and my grieving would need to happen later, separate from the immediate family circle.

Eventually the funeral home folks arrived, and this is where I was once again reminded of the hilarity that life can hand you no matter the circumstances.

These two folks, Gene and Jena, are called “Removal Technicians.”

That was new to me.

They were truly wonderful. They listened to the stories my SIL and niece needed to tell. We laughed and shared. This is part of the healing, I think. Trying to give pictures of the story of the person’s life to these people who would be taking Steven away from us; not having ever met him or known what he was truly like.

Steven owned a corvette. He was so proud and in love with this corvette. Stories of the corvette were shared with Gene and Jena and God Bless Gene, he had an idea.

“How about after we take care of Steve, after we have him on the gurney ready to go, we can wheel him out through the garage and stop in front of the corvette for one last picture. His final ride, as it were.”

Thank God my niece said, “I’m not comfortable with that.” and the horrible idea was left behind. I know Gene’s heart was in the right place, but I was barely hanging on to the hysterical laughter inside thinking of this hilariously awful suggestion.

The removal technicians gave us one more chance to say good bye before they closed the door to the bedroom and moved Steven’s body to the gurney.

They wheeled Steven out through the garage, without stopping at the corvette, and into their vehicle.

Eventually the hospice nurse left, and we finished watching “Where’d You Go, Bernadette.” because that is what life does. You keep breathing.

We all tried to sleep for a couple hours, and the next morning I said goodbye to my SIL and niece.

I flew back home to be picked up by my entire family at the airport. And we talked and laughed and I told them stories of the trip and they held me close in their hearts and arms as I grieved.

I miss you, Steven. Thanks for being my brother.